The role of English in education

As part of our SHAPE Education initiative, Cambridge University Press & Assessment is hosting monthly ‘SHAPE Live’ debates with experts on the future of education. On Tuesday, 24 May we discussed the role of English in education globally. Angeliki Salamoura, Head of Learning Oriented Assessment Research (English) at Cambridge University Press & Assessment, reflects on the recent event.

There is currently little doubt that governments, schools and parents around the world endorse the need for learning English as part of basic education – English can bring access to education and jobs, promote social mobility, and connect people. At its best, English can confer many benefits. Is, however, English always taught in the best possible way to realise these benefits for learners?

The latest SHAPE Live event brought together three prominent scholars to debate the issue: Professor Stephen Dobson, Dean of the Faculty of Education at Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand; Professor Lina Mukhopadhyay, from The English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad in India; and Professor Ianthi Tsimpli, Chair of English and Applied Linguistics at the University of Cambridge.

Stephen began by reminding us that in many parts of the world English is often one piece of the linguistic repertoire of a community, which includes mother tongues and other languages. It is, therefore, important to make allowances for connections between the languages and cultures in which English is embedded. In the Indonesian context, for example, there is the concept that all education should embrace values that match the culture and that teaching should be done in a holistic fashion. Sometimes, however, when English is taught in other cultures, it is about assessment rather than balancing the values that are in existence in that particular culture.

...when offering an English language curriculum in an educational system or in a school, it’s important to ensure that it complements rather than competes with curricula in the national or local languages.

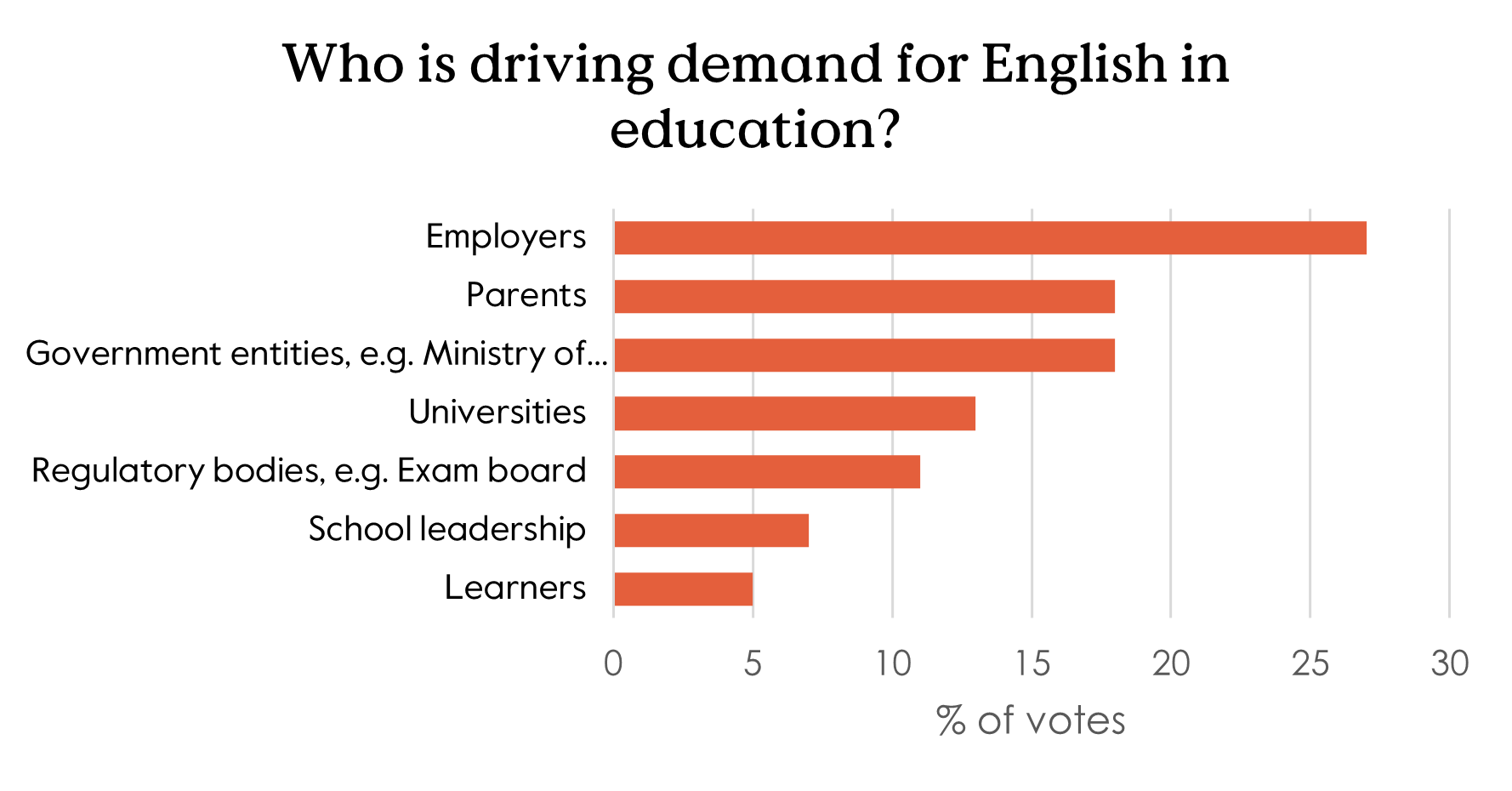

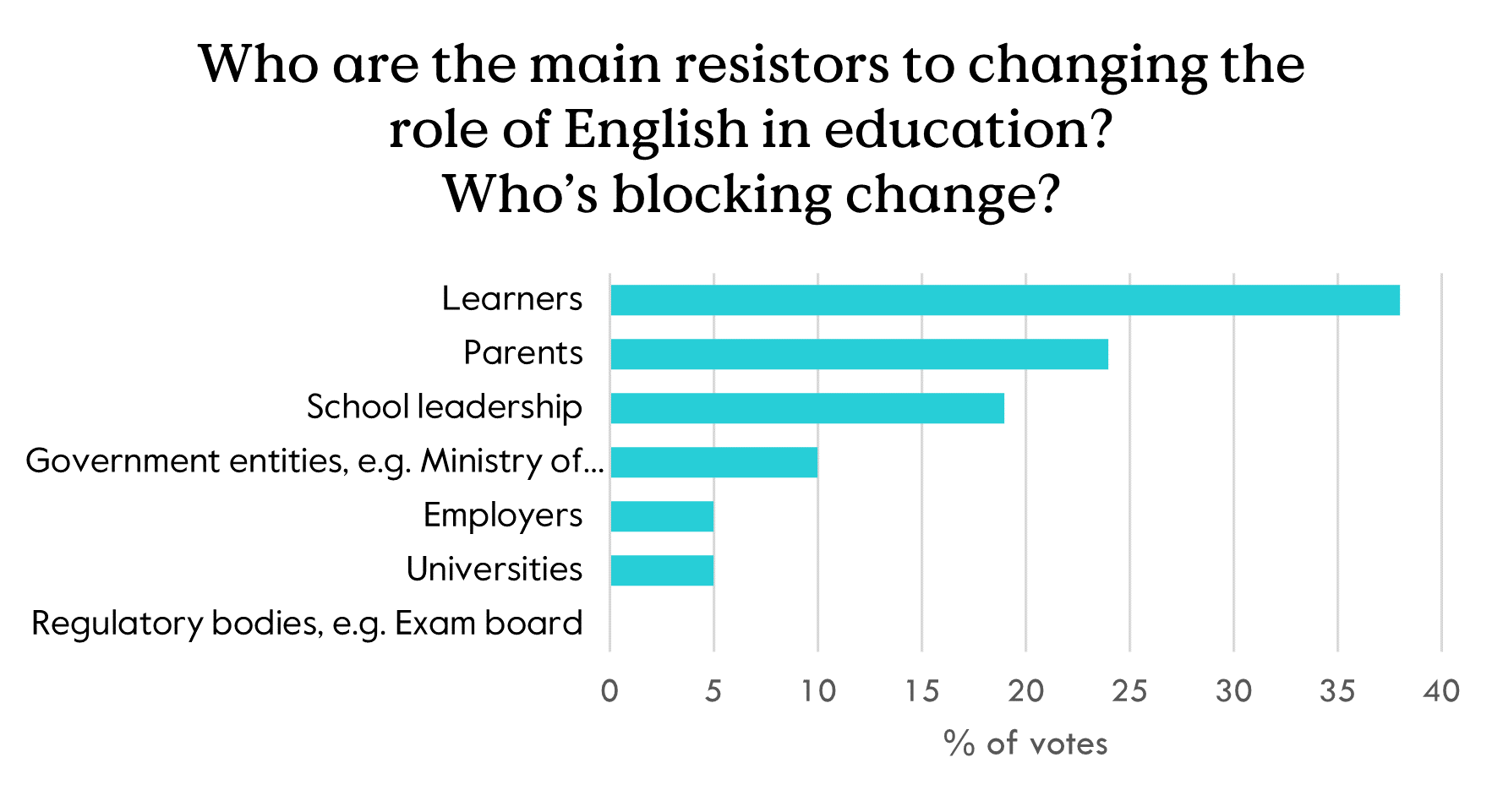

So, when offering an English language curriculum in an educational system or in a school, it’s important to ensure that it complements rather than competes with curricula in the national or local languages. Otherwise, it can disrupt national education policies and practices in non-English speaking countries. Interestingly, the audience in the discussion thought that some of the top stakeholders who drive demand for English in education, namely, governments, parents and regulatory bodies, are also the main resistors to changing the role of English in education.

Poll of participants attending the SHAPE Live session on 24 May 2022

Lina brought in her experience with schools in India. Lina and Ianthi have been working on MultiLiLa, an interdisciplinary project, investigating ways to raise learning outcomes in primary schools across India through multilingualism and multiliteracy practices. Their research examined cognitive, linguistic and mathematical abilities of multilingual Indian learners and the attitudes, language choices and practices of language and mathematics teachers.

English education is becoming more and more important in the primary school context in India and many states are considering whether they should introduce English as the medium of education from primary. However, Lina pointed out that there are challenges with this approach for a majority of students who do not encounter English outside school and, as a result, their proficiency is limited.

In these cases, their reading comprehension, which is the backbone of education, could suffer. Lina suggests that translanguaging (the use of more than one language during an activity) and other multilingual practices can significantly aid comprehension and mathematics. Rather than ‘getting lost in translation’, teachers can use the multilingual resources already developed in their students to propel their learning in a new language such as English.

Is, therefore, a better understanding of multilingual pedagogy and its efficient implementation in practice the key to the future of English in education?

Is, therefore, a better understanding of multilingual pedagogy and its efficient implementation in practice the key to the future of English in education? Ianthi’s comments nodded towards that direction. Best practice in teaching and learning English may differ for different parts of the world depending on the local context. An important variable to take into consideration here is whether the community or country is monolingual or multilingual. Where multilingualism is the norm and people do not restrict themselves to a unilingual practice in their everyday life, using translanguaging and multilingual resources to teach English (among other practices) may, in fact, be the way to go to build a gradual way of developing knowledge of English.

According to Ianthi, what we are missing at the moment at the educational level is sensitivity to diversity in terms of language practices around the world. English educators need to become aware of this diversity before they advise on which method is best to introduce English in their local context. A successful model of introducing and teaching English in one part of the world (e.g. Europe) is not necessarily suitable for the same purposes in another part of the world (e.g. India), particularly where not only the overall culture but also language culture is different. For instance, when introducing a language as the language of instruction, both teachers and learners need to have a certain minimum level of proficiency in that language for this model to work successfully. Otherwise, it may actually impede learning gains.

...in contexts where teachers and learners are multilingual, multilingual practices in teaching and learning in the classroom are advantageous and should be supported if we truly want education to help individuals flourish and realise their full potential.

In conclusion, research and practice across diverse contexts such as India, Indonesia and New Zealand supports the co-existence of English and other language curricula in ways that respect cultural and linguistic diversity and values. It also shows that in contexts where teachers and learners are multilingual, multilingual practices in teaching and learning in the classroom are advantageous and should be supported if we truly want education to help individuals flourish and realise their full potential.

Watch the recording of this SHAPE Live event which took place on Tuesday, 24 May 2022 on the Cambridge University Press & Assessment YouTube channel. You can also find out more about the SHAPE Education initiative and watch previous live events.

About the author:

Angeliki Salamoura, Head of Learning Oriented Assessment Research (English) at Cambridge University Press & Assessment

Angeliki has over 25 years of experience in the field of English education, as a teacher, researcher, research manager and assessment and learning specialist. As Head of Learning Oriented Assessment Research (English), she leads on research into language learning, integrated learning and assessment and the CEFR. Angeliki also has extensive experience in impact and education reform projects, ranging from CEFR familiarisation and benchmarking to test and programme evaluation. In this context, she has led impact assessment projects in the K-12 and vocational sectors in Europe, Asia and South America. She is one of the contributors to the PISA 2025 Foreign Language Assessment Framework and has been on the Experts Group who advised on the constructs of the accompanying PISA 2025 Background Questionnaires.