Grades, standards and the pandemic

The cancellation of GCSE and A Level exams during the pandemic changed the way the grades were awarded. School closures and isolation absences meant that students also missed out on opportunities to learn, and experienced varying degrees of learning loss. But what do grades awarded during the Covid pandemic mean? How do they compare to grades awarded in previous years?

In this blog I will talk about the uses of exam grades in relation to how they have been awarded in order to reassure students and other stakeholders of the value of these grades.

How do we use grades?

Exam grades are a normally a measure of student attainment and measure the knowledge, skills and understanding (KSU) of someone in a particular subject. They are awarded on the results of exams that are usually taken at the end of two or more years of learning and preparation. They have multiple uses; they allow us to:

- compare students who have taken the same or a similar exam e.g., a student with an A has demonstrated more KSU than a student awarded a C

- decide whether someone has enough (specific) knowledge to study a particular course

- decide whether the person has the potential to succeed (e.g., at a course or job).

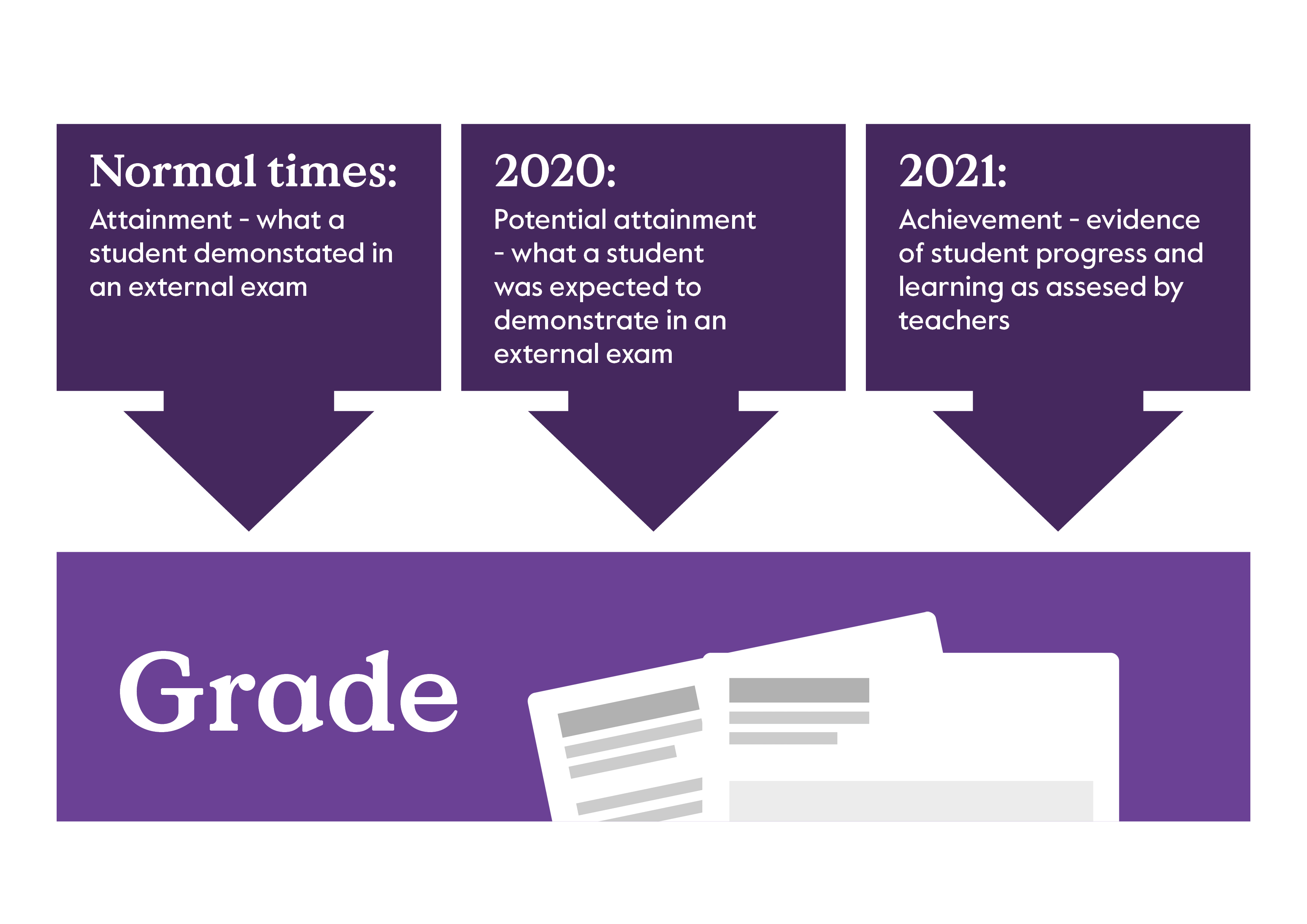

In normal times these uses coexist and their flexibility is in fact a real benefit for students, universities, and employers alike as it avoids the need for multiple forms of assessment. The way grades were awarded in the extraordinary circumstances created by the response to the pandemic has resulted in questions around their use. Can we use the pandemic grades in the same way and for the same purposes?

Grades and the pandemic

The 2020 grades were (or were based on) the centre assessed grade – an estimate of how a student would have performed on the exam. This was possible as the students had studied the bulk of the course content. This shifted the grade awarded from one of attainment in an exam to one of potential attainment.

The amount of learning loss for the 2021 students meant this approach was not possible and teacher assessed grades were estimated based on multiple sources of evidence collected in schools - this caused some tension between the uses. The underlying issue here is knowledge – students haven’t had the opportunity to learn as much as in normal times. This is further complicated by schools differing in their approach to teaching the content and differing circumstances and levels of disruption (e.g., access to technology (1) , closures, absences etc.). Here we see the shift in grade from attainment in an exam to evidence of progress and success in learning - that is, achievement on the course - as assessed by teachers. While students had to perform at an expected level on the content taught to achieve the grade, the breadth of knowledge varied from school to school.

Returning to our exam uses, in all three scenarios we can assess a student’s potential to succeed. When comparing students, we can still make reasonable comparisons though the differentiation may not be as precise as in normal times. It is important we consider additional evidence such as applications forms, interviews, personal statements, etc., to help make the best decisions. Where the content knowledge is less broad, for understandable reasons, this may have implications for further study of that particular subject. Universities and colleges can help by providing the opportunity for students to develop KSU in the areas needed.

Standards and the pandemic

In normal times the aim is for examination standards to be maintained from year to year so my B grade obtained in 2017 carries the same meaning as yours in 2019 and similarly stakeholders can use them to make the same sort of decisions. But what about pandemic grades? This year, schools and colleges were asked to ensure that it was no easier or harder for a student to achieve a particular grade compared to previous years. This was the same advice that was given to schools and colleges in summer 2020 – the expected performance standard for a grade did not change. As part of their internal quality assurance, centres were asked to consider the grades for this year’s cohort compared to cohorts from recent years when exams have taken place (2017, 2018 or 2019), where they could be confident that a consistent national standard was applied.

Understandably, the focus over the past two years has been on students not missing out on future opportunities. This will have had the natural consequence of more higher grades being awarded than in previous years, since borderline students will have been given the benefit of the doubt. This is a rational response to uncertainty (2). We can think about the outcome as a positive or legitimate instance of grade inflation, a pragmatic solution to the challenges of an exceptional year.

In normal times the grade carries the standard. However, during the pandemic grades were awarded by a different process, by teachers, so there has been a break in the process. This change in the way students were measured has resulted in a shift in standards. But what happens next? The next blog in the series will explore this.

This blog is the latest in our series of blogs based on our outline principles for the future of education through which we are dissecting the importance of textbooks and other learning materials, the curriculum and assessment, as well as approaches to learning and schools themselves.

About the author

Lucy Chambers, Senior Research Officer

Lucy joined Cambridge University Press and Assessment in 2004 and has worked on projects including developing methods and metrics to monitor the quality of marking, developing data and information reporting systems and examination comparability. Her current interests include the moderation of school-based assessment and investigating the validity of comparative judgement.

Lucy has taught English in Japan, the Czech Republic and the UK and holds an MA in Applied Linguistics from Anglia Ruskin University, a PGDip in Health Psychology from City University and a BSc in Psychology from the University of Stirling.

References

(1) Has Covid-19 highlighted a digital divide in UK education?

(2) Benton, T. (2021). On using generosity to combat unreliability. Research Matters : A Cambridge Assessment publication, 31, 22–41