How can research be used in agile developments?

In recent years more and more organisations are moving to an agile way of working. The Agile Organisation in the UK defines it as:

“….bringing people, processes, connectivity and technology, time and place together to find the most appropriate and effective way of working to carry out a particular task. It is working within guidelines (of the task) but without boundaries (of how you achieve it).”

OCR’s Research and Thought Leadership Lead, Sarah Hughes, reflects on the benefits of applying this way of working to research.

I trust agile working

Before starting a new role leading research and thought leadership, I had prior experience of working in agile development as the user of a digital tool being developed. I remember having regular meetings with people who had job titles I didn’t really understand, but where everyone was listening intently to each other.

- I learnt the importance of talking with clarity about what functionality I wanted.

- I gave up giving pleasing feedback and became direct about what was and was not working for me.

- I did some sharply focussed prioritising.

- We were planning something for use next week not some point in the future.

- We became a close-knit team of designers, researchers and users.

- Most significantly and importantly we got a tool which really worked, was being used after just a few weeks and was smooth to use.

When I began my new role in a new team developing digital educational products in an agile way, I arrived with a positive attitude to agile working but a vague understanding of what it really is. I also brought with me a vision of the team developing beautiful digital educational tools each offering something that does not yet exist to teachers who can’t wait to get their hands on them.”

I joined the new team in Sprint 3; product designers were already on their journey to discovering the problems to address. Sprints were two-week cycles with daily stand-ups and end of sprint show and tells and retrospective meetings. I felt like I was standing on the station platform watching the ‘design train’ leave the station waving both hands in the air and bellowing ‘What evidence are you using to make decisions?!’ To my relief, key design decisions had not yet been made - these were planned for later. Phew, there was a chance for me, and the research I do, to have impact!

What kind of ‘research’?

Everyone was talking about ‘research’ – customer research, user experience research, market research. In some ways these are not so different from each other or from academic research. But what did It mean for me? Most of my experience has been in academic research. I was baffled and panicked. I needed answers:

- where does academic research fit into this?

- how do I make sure the right questions are being addressed?

- how do I provide evidence in the right form and at the right time for decision making?

- how do I do this without jeopardising the quality of the research?

Someone suggested that academic research could start once we had a minimum viable product and it would confirm that the design was right. ***Alarm bells!!*** Research is not a confirmatory exercise to justify decisions already made. Yes, the time will come for post hoc evaluation but academic research can, and should, proactively inform decisions. And it often does, but only when decision makers and researchers plan far enough ahead. This is not always the case: I have seen first-hand the frustration of decision makers needing evidence quickly and of academic researchers not being given enough time to deliver evidence so that it can impact.

The research process

Right now, the project needs literature reviews: decisions can benefit from knowing what is already out there. Typically, an academic literature review takes months. I had visions of my update at the next 30 daily stand ups - ‘today I am reading literature’ – confirming perceptions that academic research is just not responsive enough.

I’m familiar with the academic literature review process, its shape, its timing. It’s not precisely linear but these activities are universal.

So, how do I get evidence to the design team in the right form and at the right time? I streamlined the research process.

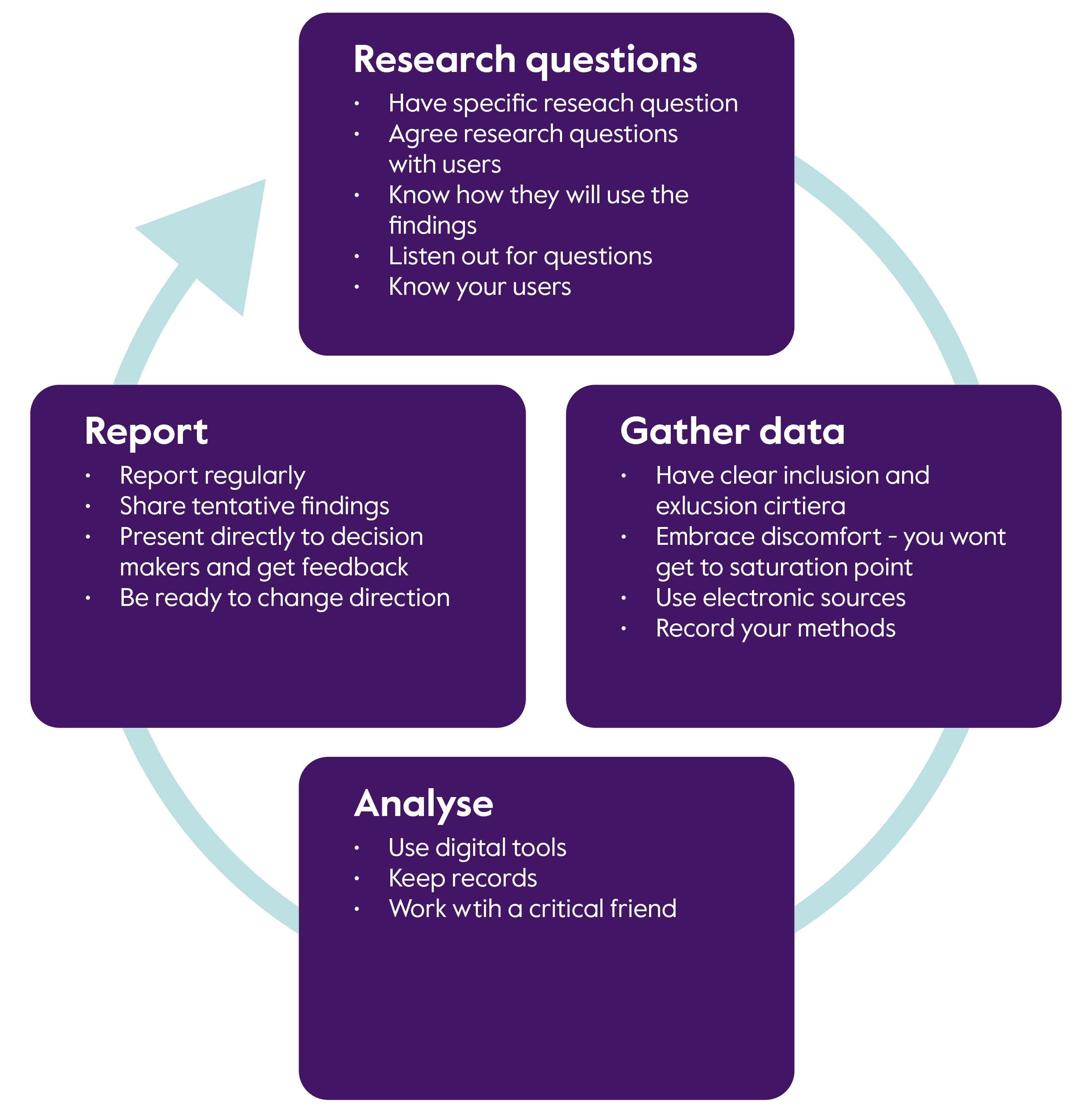

1. Define your research questions

- Take time to identify research needs with the design team, typically at sprint planning.

- Craft specific research questions. ‘What is the purpose of computing education?’ is not going to work; whereas ‘What are the constructs taught and assessed in computational thinking education?’ can be addressed in a sprint or two.

- The design team come up with the questions. Researchers refine those questions and then answer them.

- Ask the decision makers – How will you use the evidence to make decisions? Use their answer as a focus.

- Be present. Attend show and tells, retrospectives, sprint planning, daily stand ups – and always be listening to see whether the question you are answering are still relevant. And act quickly in response.

- Stick questions which are interesting but not essential in the backlog. These will very quickly fall off the bottom of the list.

- Know what your research users already know. Our designers are experts in their specialist areas – there is plenty that they already know.

2. Gather the literature

- Know how much data is enough. Have clear inclusion and exclusion criteria which directly focus on your research question. A few quality key texts in the area are enough. If you can find a recent PhD or systematic literature review on the topic then all the better - someone has already done the hard work to a high standard.

- Be prepared for the discomfort of not reaching saturation point (that stage when the same things keep coming up in the literature and you think, ‘my job here is done’).

- Speed things up with digital tools. Digital resources are widespread and include huge numbers of data bases; ebooks arrive instantly; use your librarian.

- Briefly record your methods. Which search engines did you use? Key terms? Rationale for choosing particular articles?

3. Analyse and synthesise

- Use qualitative data analysis software. I use MaxQDA. Not only does this help answer the current question efficiently, but when another question arises it’s easy to search the literature that is already tagged.

- Keep records to allow anyone to understand how you made conclusions.

- Work with a critical friend (or two) to quality assure your work. Have other researchers review your themes, interpretations and conclusions.

4. Report

- Report tentative findings, even if you fear that they are not ready to share. If further work shows the tentative findings to be wrong or misleading, say so!

- Don’t be precious about look and feel of your findings. Instead of formal written reports, I show the research users my working notes.

- Present your findings directly and often, at show and tell meetings. But not only there, I use daily stand ups to flag a key finding and point to where to find out more.

- Present findings orally. Talk through your findings and get reactions there and then, invite questions. And be prepared to change direction.

- Tell the story and, where you can, use quotes, video and visuals to help.

5. And…

- Evaluate impact. Record what decisions were made.

So, what does this mean…

For research management?

Processes will need adapting. Ringfence research capacity, even if you can’t describe in advance exactly what researchers will be addressing, be assured that research will be needed.

For research users?

- Users can adapt their thinking in response to the research findings they receive as they receive them (rather than after ideas become embedded)

- They can ask questions directly to dedicated researchers

For researchers?

On top of the usual research skills, and an understanding of and commitment to high quality research, researchers also need these skills and mindsets:

- flexibility:

- to ride the waves of new research questions and directions

- in their belief about what the ‘correct’ research process looks like

- resilience

- active listening

- concise and engaging communication

All of which can be developed whilst researching in an agile environment.

About the author

Sarah Hughes is Research and Thought Leadership Lead at Cambridge University Press & Assessment where she carries out and applies research to support assessment designers of next generation products. She has taught in primary schools and been a researcher for UK and international awarding bodies and government agencies. Her particular research interests relate the digital teaching and learning and the impact of research on practice and policy.