Learning in crisis: why the turtle, not the hawk, should guide international education donors

Prema Clarke is author of Education Reform and the Learning Crisis in Developing Countries. In her book, she argues that there is an urgent need to rethink research and evidence generation in order for donors to more effectively collaborate with local partners for education reform.

For several years now, the international education community has recognised that the developing world is facing a learning crisis.

This is despite huge efforts by governments, and local and international organisations to effect change.

I have particular insight into the work of the international donor organisations that partner with governments and organisations in developing countries to improve education. They’ve spent billions of dollars each year for decades in an effort to achieve this.

I’ve spent much of my career working for such organisations, collaborating with local partners in low-income countries spanning South Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Pacific.

But this effort has not shown signs of bearing fruit in terms of the ultimate goal of education - learning.

From hawk’s eye to turtle’s feet

I am deeply aware of what can be done with the power, thought space, and funding that is represented by the donor community. Especially when collaborating closely with local governments and organisations which are determined to tackle the learning crisis.

Working in partnership, they can help children across the developing world to improve the skill and knowledge needed to become adept and productive as citizens.

But the donor community must rethink their approach to support countries in addressing their learning crises. In particular, there is an urgent need to rethink how they go about research and evidence generation.

One might categorize the donors’ prevalent method of evidence generation as a hawk’s eye view. A hawk can see with amazing clarity and breadth from a great distance; it can move with great agility toward the object that has been identified. Yet a hawk’s eye view does not enable an understanding of how systems in developing countries operate out of their own worldviews, habits, institutionalized practices, job roles, and organizational networks.

As a result, donor interventions using a hawk’s eye view haven’t integrated with the everyday mechanics of delivering education in a developing country.

Instead of this hawk’s eye view, I would argue that it is crucial to take a different approach in order to fully understand the ecosystem driving education in developing countries.

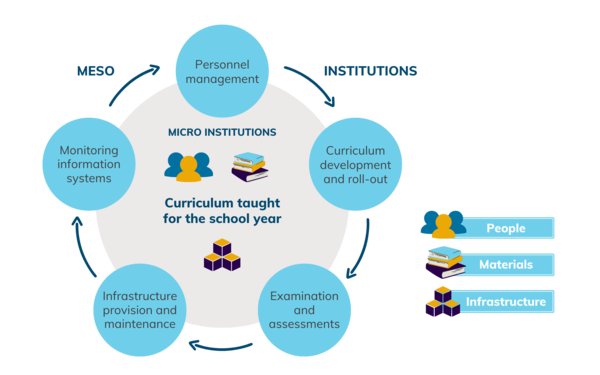

This needs to be viewed on both micro and meso levels. The micro level refers to schools and what happens in the classroom, while the meso level refers to the institutions that operate to make teaching and learning function on the ground.

Micro and meso level entities have to interact, coordinate, and work together. After all, any intervention in education has fuzzy contours making the effective functioning of one entity dependent on another. This must apply in the long term; learning is not a short-term activity, but a work in progress spread over many school years.

Take, for example, teachers’ work in the classroom. At a micro level, teachers’ work interacts and blurs with the background that each student brings to the class. So, any attempt to improve teacher content knowledge and classroom pedagogy cannot help learning if there is no attention paid to the corollary process of understanding the cognitive abilities and cultural models that students bring with them to the classroom.

To help capture the formation, functioning, and character of micro and meso level institutional dynamics in a country, interventions have to build on history, local and regional cultural and social context (or milieu), as well as embedded cultural mindsets at micro and meso levels.

In contrast to a hawk’s eye approach, achieving this requires a turtle’s feet approach. Turtles are deliberate in their movement using their feet and eyes to sense how to navigate their surroundings, observing and recognizing the lay of the land and the potential dangers relevant to where they want to go. They use close-to-the-ground data to live, move, and procreate within a complex world that traverses land and water.

A turtle’s feet approach involves carefully surveying micro and meso level institutions before moving ahead with interventions. Adopting this approach would enable donors – in partnership with local governments and institutions – to understand ways in which the history, milieu, and mindsets of meso level institutions constrain or support micro institutions in a country. And it would ultimately inform the best place for donors to put their money.

The role of a comprehensive and detailed knowledge base

So, donors need an in-depth grasp of ecosystems if they are to fulfil their role, alongside local governments and organisations, of designing and implementing appropriate and targeted interventions that promote student learning.

Yet, as it stands, certainly among donors, there is scarce knowledge and understanding of how micro and meso level institutional domains function in developing countries.

This is partly due to the predominance of quantitative approaches in the last few decades. These approaches have little potential to reveal detail, nuance, and meaning. So, other techniques are needed to understand micro- and meso-level institutional levels.

Qualitative research, which has had limited use in the past, has the potential to assist in understanding those three key factors: history, milieus, and established mindsets. That includes drawing on research from local organisations and building up local research capacities; much like the Cambridge Open Equity Initiative that supports authors in low- and middle-income countries who wish to publish their research open access but do not have access to funding.

Once there is a reasonable availability of information on how institutions, agents, and inputs function at micro and meso levels over a school year and qualitative research has addressed the earlier gaps in how this ecosystem functions, a fit-for-purpose mixed methods strategy for evidence confirmation and transformation would be helpful.

By taking this approach to evidence generation, international donors would better equip themselves with an understanding of the complex and unique ecologies that characterize school systems in developing countries. They’d then offer significantly greater potential to be an effective partner on the design of creative and relevant strategies and interventions to address the learning crisis.

Prema’s book, Education Reform and the Learning Crisis in Developing Countries, is published by Cambridge University Press.