Covid’s impact on education: what have we learned after more than two years?

In a three part series for International Day of Education, Dominique Slade, Head of Education Content & Solutions at Cambridge Partnership for Education, considers lessons for education delivery since the start of the Covid pandemic almost three years ago.

As many of us are rediscovering the pleasure of spending time with family and friends, or sharing exciting live sports or entertainment events with others, we are also gradually coming to terms with the fact that we’ll have to learn to live with COVID-19 as we have other viruses.

At the same time, it has become clear that climate change is one of the most urgent priorities facing the world today; the refugee crisis is a global issue that should concern us all; and the war in Ukraine threatens the world order and brings the prospect of a global recession.

In this context, it is becoming clear that the world will not go back to what it was before the global pandemic, there will be no ‘going back to normal’. Instead, we must accept that we are emerging into a more VUCA world than ever.

There will be no ‘going back to normal’. Instead, we must accept that we are emerging into a more VUCA world than ever.

VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous) is an acronym originally used to describe the unfamiliar post-Cold War era and today used more generally to describe the world that all sectors, including education, must learn to navigate.

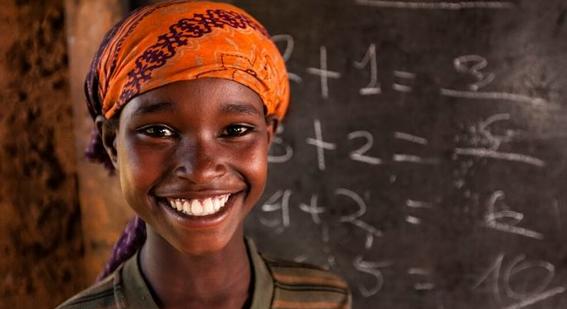

The pandemic has increased inequalities in education

At the start of the pandemic, when schools closed all over the world, pre-existing inequalities in access to quality education were revealed, not only inequalities across countries, but also within countries.

More than two years on, these inequalities and their negative consequences for both individuals and communities keep growing and are vividly described in the Human Rights Watch report ‘Years Don’t Wait for Them: Increased Inequalities in Children’s Right to Education Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic’.

The report is based on over 470 interviews with students, parents and teachers in 60 countries. It shows how many children were not given the opportunity, tools or access needed to keep on learning during the pandemic. As a result, school closures did not affect all children equally. The report goes on to show that the lack of action from governments in addressing inequalities in education creates a vicious circle that keeps, at best, perpetuating and, at worst, increasing the problem.

But it is also encouraging to see that governments are starting to recognise the negative impact of these inequalities, not only as an issue affecting certain groups, but also affecting the very fabric of their societies.

This was evident, for example, during the Recover Learning and Rebuild Education in the ASEAN Region Roundtable, which took place in March 2022 and brought together ASEAN Ministers of Education, UK government officials and education specialists to discuss education challenges following the COVID-19 pandemic.

A significant topic of discussion was the impact of school closures on vulnerable learners. The groups identified as the most at risk in the region were younger learners at serious risk of losing their foundational learning; secondary-level learners dropping out of education because of poverty and the need to work or marry to support their families; and learners in technical and vocational education no longer able to experience work settings or complete on-the-job training.

Targeting these vulnerable groups was identified as a priority to address not only learning loss in the region, but also the longer-term negative impact on countries’ socio-economic future, showing a promising move in this direction.

The scale of global learning poverty is unprecedented

In 2019, the World Bank and the UNESCO Institute for Statistics introduced the concept of learning poverty based on the percentage of young people unable to read and understand a simple text by the age of 10.

This new indicator reflected the need to keep track of the worrying fact that, despite the significant progress made in the past 20 years to achieve universal access to primary school, a large proportion of children are still left behind because they are not acquiring basic reading skills.

A large proportion of children are still left behind because they are not acquiring basic reading skills.

This new indicator provides a useful link between education and other related Sustainable Development Goals: levels of learning poverty are a threat to countries’ efforts to build the human capital they need to ensure socio-economic development and undermine poverty reduction. Therefore, there are major implications for countries’ future prosperity.

According to the World Bank, even before the pandemic, 53% of children in low- and middle-income countries couldn’t read and understand a simple story by the end of primary school – and in poor countries, the level was estimated to be as high as 80% – questioning whether the UN Sustainable Development Goals could be achieved by 2030.

More than two years on, the picture looks even bleaker. As reported by Jaime Saavedra, World Bank Global Director of Education, in his opening speech at the World Education Forum in May 2022: 53% learning poverty before the pandemic could increase to 70% according to the latest simulations.

New data presented in ‘The State of Global Learning Poverty: 2022 Update’, a joint publication by the World Bank, UNICEF, FCDO, USAID and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, in partnership with UNESCO, confirms that the pandemic has sharply increased learning poverty, with school disruptions driven by COVID-19 exacerbating the severe pre-pandemic learning crisis.

The role of schools goes beyond education

At the peak of the pandemic in April 2020, more than 90% of schools in the world were closed for varying lengths of time. The impact of these closures revealed that schools play an essential role in communities that goes beyond education; during school closures, children’s health and safety were jeopardised, with domestic violence and child labour increasing.

More than 370 million children globally missed out on school meals, losing what is, for some children, their only reliable source of food and daily nutrition. Similarly, the mental health crisis among young people reached unprecedented levels and advances in gender equality were threatened, with school closures placing an estimated 10 million more girls at risk of early marriage and dropping out of school in the next decade.

In the aftermath, the message from the Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel in their 2022 report ‘Prioritizing Learning During COVID-19: The Most Effective Ways to Keep Children Learning During and Post-Pandemic’ is clear:

“The large educational, economic, social and mental health cost of school closures and the inadequacy of remote learning strategies to substitute for in-person learning suggest full or partial school closure should be a last resort in government COVID-19 mitigation strategies.

“Because losses in human capital reduce income and productivity throughout a child’s life, the impacts of school closures will last longer than disruptions in many other sectors. This suggests that keeping pre-schools, primary and secondary schools fully open should be prioritised over keeping open non-education sectors where disruptions cause only shorter-term losses.”

The pandemic has highlighted the importance for governments to develop resilient education systems that are able to provide remote forms of quality learning at scale in the future, so they are better prepared to address the consequences of our increasingly VUCA world.

The pandemic has highlighted the importance for governments to develop resilient education systems that are able to provide remote forms of quality learning at scale in the future.

However, it is also clear that schools are likely to remain the main model of education delivery in the foreseeable future. Therefore, finding a way of bringing together remote learning and schools to develop education systems that are more effective, equitable and resilient will be one of the challenges and opportunities for education in the future.

There is a new sense of urgency and ambition for education

Alongside the alarming picture described above, we can feel a new sense of urgency, ambition, and possibility in the air. This is based on the shared belief of the unique role that education can and must play in preparing the younger generations not only to live in this uncertain, VUCA world, but also to be committed to and capable of transforming it.

This was palpable during the three days of the Education World Forum that took place in London in May 2022, during which Ministers of Education from 116 countries described a pivotal moment, highlighting a series of choices that will impact not only the education of a generation, but the future of the world.

This same feeling of urgency and ambition was evident in the United Nations’ preparations for the Transforming Education Summit in September 2022 in New York. In its keynote address ‘The Transforming Education Summit: a turning point for education’, Leonardo Garnier, Special Adviser to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, declared that:

‘The Summit [is not] an end in itself, but rather a turning point: it pretends to ignite a movement for the transformation of education that goes beyond business as usual, beyond doing things a little faster or a little better, and beyond merely recovering from the pandemic. We must aim higher. We must reimagine and transform education into a passionate and rigorous process of individual and collective self-discovery and self-development, so that every student has the best opportunities to flourish in every sense.’

This new sense of shared urgency to transform education brings with it a range of exciting new opportunities. These need to build on what we have learned the hard way over the past two years, while responding to the new challenges faced by education systems all over the world and navigating the uncertainties of the post-pandemic VUCA world.

In her next post on the impact of Covid on education, Dominique will consider what new challenges we now face. If you’d like to discuss how we at Cambridge can help you tackle your unique challenges in education delivery, then please contact us.

This blog draws from our report: Covid's impact on education after more than two years.